Confidence engineering: Why your onboarding is probably too short

We added 22 steps to our checkout flow and conversion jumped 40%. Why the goal isn't minimal friction—it's maximum confidence at the moment of decision.

At Sesame Care, we ran an experiment that violated everything product people think they know about conversion optimization.

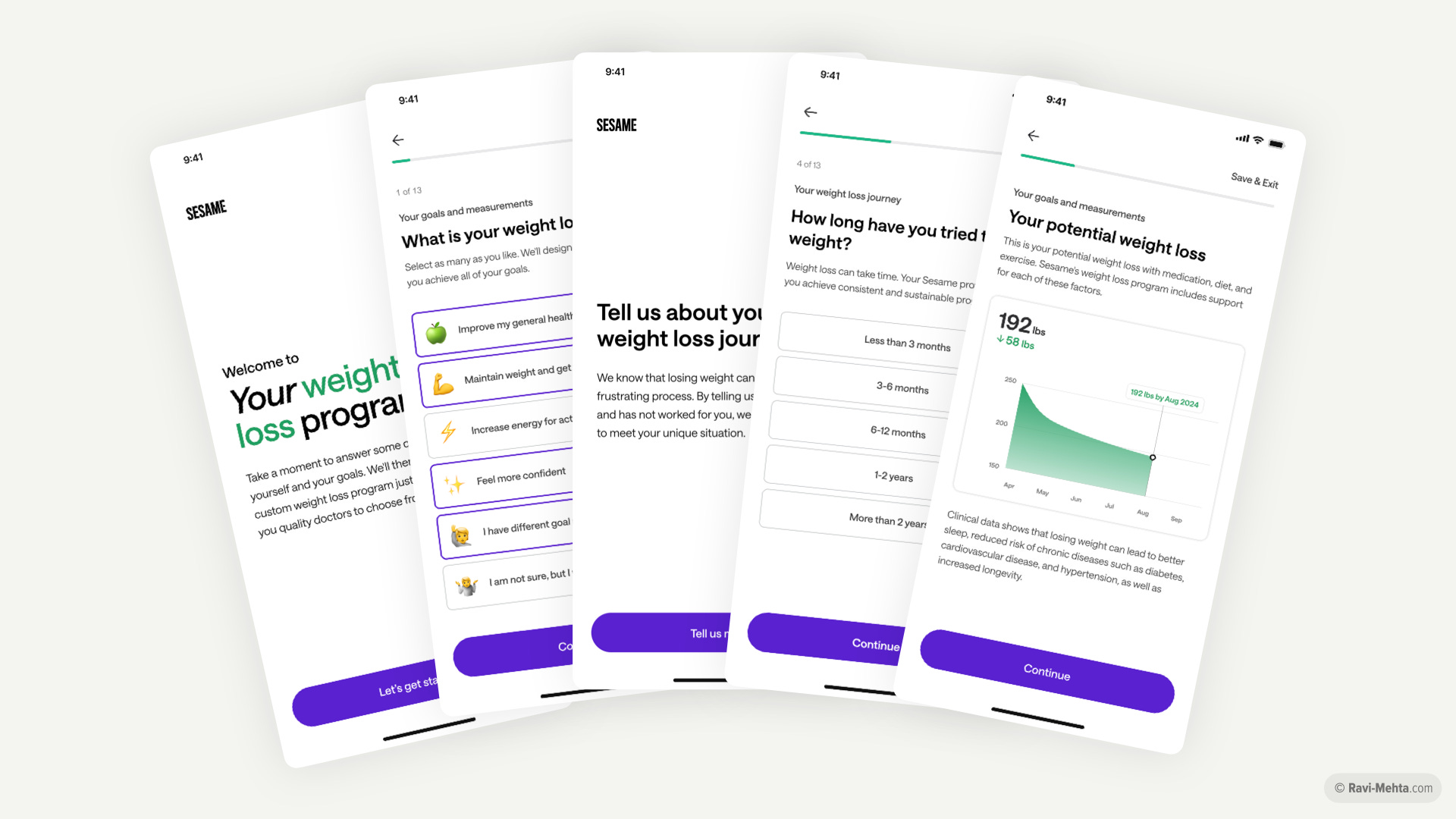

We took a three-step checkout flow for a weight loss medication program and replaced it with a twenty-five-step intake. Medical history. Lifestyle questions. Weight loss goals. Personalized projections. The works.

Conversion jumped 40%.

Not despite the added steps. Because of them.

The step-to-step completion rate is north of 99%. Each step fosters their confidence. By the time they reach checkout, they are ready. Confident. The decision feels right.

This flies in the face of conventional wisdom. We’ve been trained to believe that every form field is friction, every additional screen is a drop-off risk. Remove steps. Reduce friction. Get out of the user’s way.

But that advice is incomplete. And following it blindly can cost you conversions, customers, and ultimately the business you’re trying to build.

The Tinder paradox

Here’s what makes this interesting: I’ve also worked on products where the opposite approach is exactly right.

When Tinder launched, the dating market was dominated by Match and eHarmony. Both required 20 to 30 minutes of profile creation. Detailed questionnaires. Personality assessments. The implicit message: finding love is serious business, and we need to know everything about you.

Tinder took a different path. User’s login with Facebook (instead of setting up a new account). They pick a few photos (pre-loaded from their Facebook reel). Bios are short—only a couple of lines.

A new user could from “maybe I’ll try this app” to actually swiping on people in under two minutes.

The result wasn’t just faster onboarding. It was market expansion. Tinder pulled in millions of people who never would have created an eHarmony profile—not because they didn’t want to date, but because they weren’t willing to invest 30 minutes to find out if online dating worked for them.

So now we have two data points that seem contradictory. Twenty-five steps beats three. But also: ninety seconds beats thirty minutes.

What’s actually going on?

The wrong question

Most product teams ask: “Should our onboarding be short or long?”

The right question is: “What does a user need to feel confident at the moment of decision?”

This reframe changes everything. Length becomes a dependent variable, not an independent one. The goal isn’t minimizing steps—it’s maximizing confidence at the point where you’re asking someone to commit.

Think about this as “confidence engineering”.

Everyone in AI is talking about context engineering—giving models the right information to produce good outputs. Confidence engineering is the human equivalent: giving users the right information, at the right pace, to produce a confident decision.

Good friction vs. bad friction

The mistake most teams make is treating all friction as bad friction. It’s not.

Bad friction creates doubt. It interrupts momentum without adding value. It asks for information the user doesn’t understand why you need.

Asking a user to create a password is bad friction. It seems simple, but it’s not. It’s cognitively expensive. Should I use my usual password? Make up a new one? Do I even trust this site? Will I ever come back? The user came to experience your product. Now they’re solving a security problem instead.

Most teams treat password creation as a given—something they just have to do. It’s not. It’s one of the worst friction points in any signup flow. Tinder never asks users to create a password. An increasing number of products are following suit: magic links, one-time passwords, sign-in with Google or Apple. They’ve recognized that the best way to handle bad friction is to eliminate it entirely.

Good friction builds confidence. It demonstrates that you understand the user’s situation. It answers their questions before they ask them. It signals quality and care.

The Sesame intake works because every question serves double duty. Yes, we’re gathering medical history. But we’re also signaling: this is comprehensive care, not a pill mill. When someone is about to inject themselves with medication for the first time in their life, that signal matters enormously.

Tinder’s short onboarding works because the “Aha!” moment is different and the stakes are low. Get the user swiping, and they’ll start to experience the product’s value. The worst case? They match with someone they’re not that into, and they unmatch. Low stakes means you can shorten onboarding and accelerate time to value.

The variable that determines whether friction is good or bad isn’t the friction itself. It’s the relationship between that friction and the confidence required for the decision at hand.

When to add steps, when to remove them

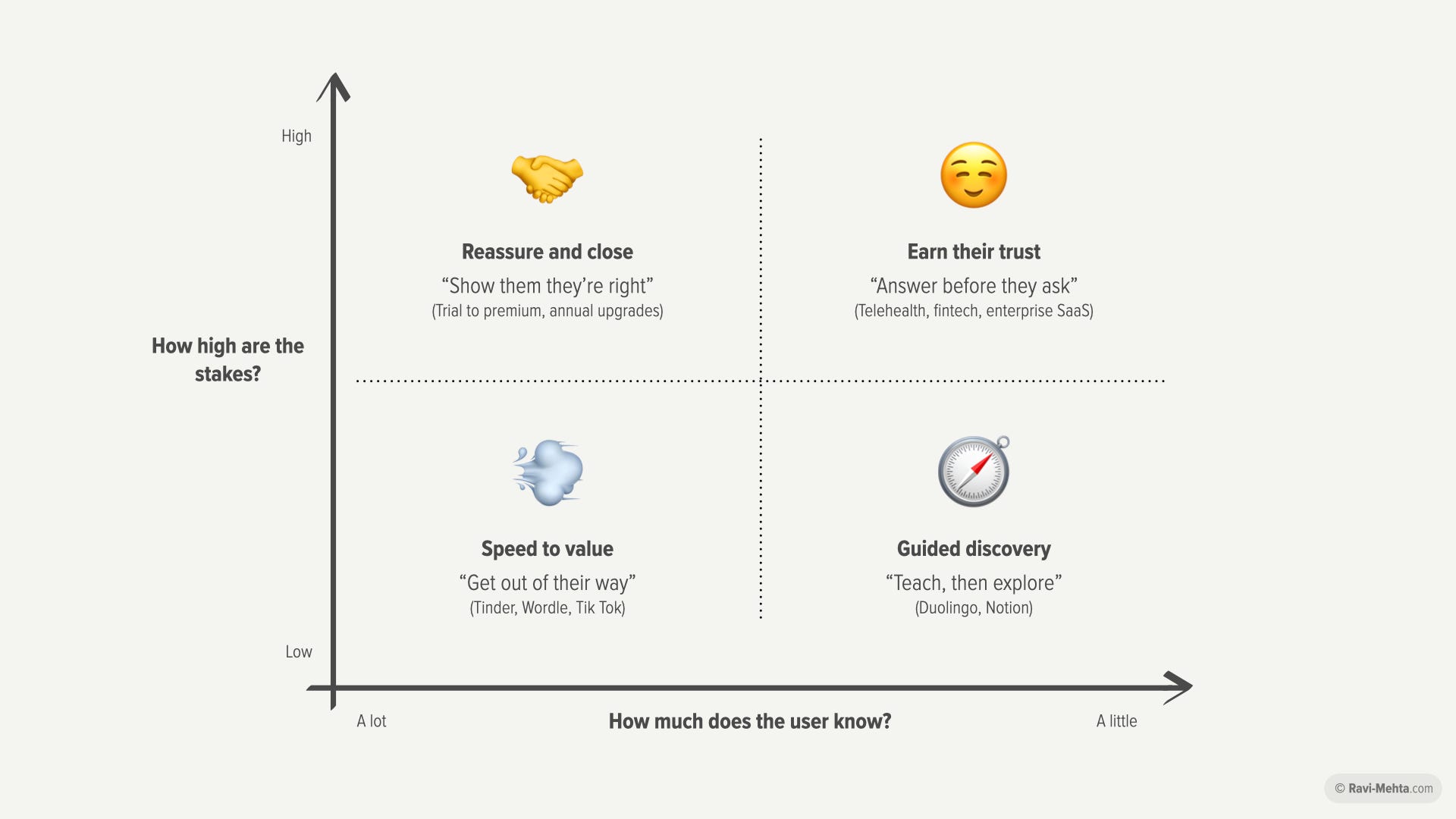

This gives us a framework for thinking about onboarding design.

Variable 1: Decision consequence

How significant is the commitment you’re asking for? A free trial signup is low consequence. A $500/month subscription is high consequence. Swiping on a dating profile is low consequence. Injecting yourself with medication is high consequence.

High-consequence decisions require more confidence. Users need to feel certain they’re making the right choice, because the cost of being wrong is meaningful.

Variable 2: Information gap

How much does the user already know about what they’re getting? If your product category is well-understood and your value prop is clear, users arrive with existing mental models. If your product is novel or complex, there’s more work to do.

Large information gaps require more onboarding—not to create friction, but to close the gap and build the confidence that comes from understanding.

Plot these two variables against each other and you get a matrix:

Low consequence, small gap: Ultra-short onboarding. Get out of the way. (Tinder, casual games)

Low consequence, large gap: Brief education, then let them explore. (New social apps, novel utilities)

High consequence, small gap: Streamlined but thorough. Confirm expectations. (Premium subscriptions in known categories)

High consequence, large gap: Extended onboarding that builds confidence through comprehensiveness. (Healthcare, financial products, enterprise software)

Sesame’s weight loss program sits squarely in that bottom-right quadrant. High consequence, large information gap. The 25-step intake isn’t friction—it’s confidence engineering.

The Psych budget

Darius Contractor has a framework called Psych’d that adds precision to this thinking. The idea: users arrive at your product with some motivation—they are psych’d to get started. Your onboarding flow either fosters or squanders that initial motivation. We can model this behavior as a “psych budget” that gets added to or subtracted from as the user moves through your product.

Some steps add psych points. Personalized content. Value delivery. Moments that make users feel understood or excited.

Some steps subtract psych points. Password creation. Unexpected form fields. Anything that feels like bureaucracy rather than value.

Power tip: Pay careful attention to how you phrase questions to the user. A subtle change can make the difference between a question the user knows the answer to, or one that gets them stuck and likely to churn. For example, we originally asked users in Sesame’s intake, “What was the date of your last physical?” Think about it… do you know the answer to that question? We changed to” “Have you had a physical in the last six months?” Much easier to answer

The key insight: a good onboarding isn’t necessarily short or long. A good onboarding keeps Psych high by building confidence and delivering value throughout the experience.

Let’s look at two examples—one that gets it right, one that doesn’t.

Calm, a promise delivered

Open the Calm app and you immediately hear rain sounds. Before you’ve created an account. Before you’ve entered any information. Before you’ve done anything at all.

Calm’s promise is that it will make you calmer. And they deliver on that promise in the first three seconds of interaction. Their commercials do the same thing—fifteen seconds of rain sounds, no pitch, no features, just the product working.

When you can deliver value during onboarding, length becomes almost irrelevant. Users aren’t tolerating your intake process in hopes of future value. They’re already getting value. Every additional step is just more of what they came for.

The question worth asking: can your onboarding be the product? Can the process of getting set up actually deliver the value you’re promising?

For Calm, this is natural. For other products, it requires creativity. But when you can pull it off, you’ve solved the confidence problem from a completely different angle—not by building confidence through information, but by building it through experience.

“Just for You”, a promise broken

Here’s a counterintuitive example from my time at Tripadvisor. We built a new recommendation algorithm that showed users hotels they were more likely to book based on their browsing history. In blind testing, it outperformed our default ranking. People converted better.

Then we branded it “Just For You” and made it our default sort order.

Conversion dropped.

Same algorithm. Different results. Why?

Before, our algorithm was working silently in the background. Now, travelers felt like we were making decisions for them—and they didn’t trust us to know what was “Just for You”.

The feature introduced doubt. Travelers came to Tripadvisor psychd to use authentic reviews to make a better decision. “Just For You” threw a wrench in that. What invisible forces were pushing them toward certain hotels? Were we hiding great hotels? They wanted the transparency of traveler reviews, not the opacity of an algorithm.

The lesson: confidence isn’t just about what you deliver. It’s about whether users feel in control of their decision.

The messy middle

Onboarding teams often hit a common failure mode. They want to keep the experience short, but they sneak in extra questions to appease various stakeholders. A few fields here, a quick survey there.

The result? An onboarding without a clear strategy. Not short enough to feel effortless. Not long enough to feel comprehensive.

This is the death zone. It’s where products land when teams compromise between “we need more information” and “we should reduce friction”—without asking the harder question: what do users actually need to feel confident?

The death zone creates the worst of both worlds. Enough friction to lose impatient users. Not enough substance to win over uncertain ones.

Pick a lane. Get radically short and remove everything that isn’t essential. Or get comprehensively long and make every step build toward commitment. Or deliver value so immediately that length stops mattering.

Just don’t split the difference.

Applying “confidence engineering” to your product

Here’s how to put confidence engineering into practice:

First, identify your “Aha!” moment. What’s the experience that makes users understand your value? For dating apps, it’s getting into a conversation. For healthcare, it’s the doctor consultation. For productivity tools, it’s completing their first task. For Calm, its… feeling calmer. Everything in onboarding should be building toward that moment.

Second, assess the stakes… from the user’s perspective. What are you asking users to commit to, and what’s the cost if they’re wrong? Be honest about this. A free trial with easy cancellation is low consequence. A annual subscription with complex setup is high consequence.

Third, audit every step. Does this build confidence or create doubt? Does it signal quality or feel like bureaucracy? Would removing it make users more or less certain about their decision?

Fourth, look for value delivery opportunities. Can any part of your onboarding actually be the product? Can you demonstrate value before asking for commitment?

The goal isn’t short onboarding or long onboarding. The goal is confident users who are ready to say yes.

The conventional wisdom—reduce friction, remove steps, get out of the way—isn’t wrong. It’s just incomplete.

Friction is a tool. Like any tool, it can be used well or poorly. Bad friction creates doubt and kills conversion. Good friction builds confidence and earns commitment.

The discipline of confidence engineering is learning to tell the difference—and designing onboarding that gives users exactly what they need to feel ready for the decision you’re asking them to make.

Sometimes that’s 90 seconds. Sometimes that’s 25 steps. The number doesn’t matter.

What matters is whether users arrive at the decision point confident that they’re making the right choice.

fast or thoughtful as function of consequence