The spec is dead, long live the spec!

Prototypes are the new specs and specs are the new.... source code?

Over my career, specs have gotten shorter and shorter. When I started at Microsoft, the worth of a PM was measured in the weight of their specs. Years later, at Tripadvisor, we mythologized the PM who brought a spec—scribbled on a napkin—to Product Review.

Product teams often treat specifications like paperwork—a necessary evil before the "real work" of shipping. Engineers get celebrated for elegant code, designers for beautiful UX. PMs get kudos for delivering impact. But specs? They’re typically rushed through, tossed aside, forgotten.

This was always a mistake. In my Product Competency Toolkit, Feature Specification sits at the top—first among twelve competencies—for a reason. It underpins Product Execution, along with Product Delivery and Product Quality.

Flawless execution is the foundation of good product management, and a great spec is the starting line.

Today, the way we build is shifting. Engineers are getting faster—much faster. AI can turn rough ideas into working code in minutes. The bottleneck is no longer building. It's knowing what to build, and aligning the team around those requirements.

Suddenly, the humble specification isn't ephemeral paperwork. It’s the foundation of product management—it's becoming the source code itself.

Why PMs are suddenly the bottleneck

In his recent talk Building Faster with AI, Andrew Ng noted an unprecedented trend:

"For the first time in my life that I saw managers proposed to me having twice as many PMs as engineers. I still don't know if this proposal is a good idea, but I think it's a sign of where the world is going." —Andrew Ng

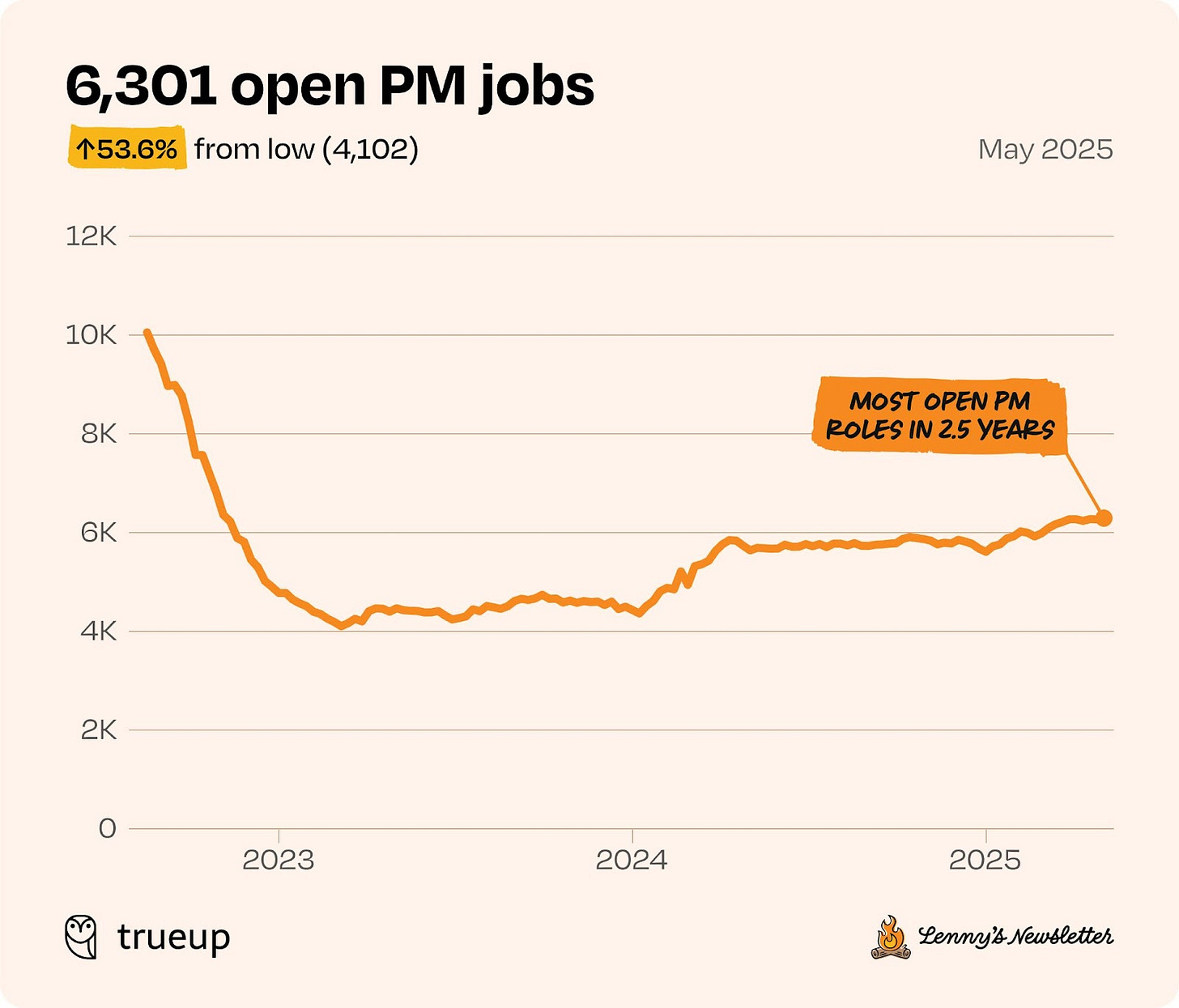

This validates what we predicted in our previous post: as engineers deliver many times faster with AI, companies need more PMs to support those productive engineers, not fewer.

As product delivery accelerates, that puts intense pressure on every other aspect of product management—understanding customer needs, crafting the right features, validating impact.

And all of that pressure gets focused into one artifact—the spec.

Specs—the new source code

In traditional software development, programmers write human readable “source code” which gets compiled into highly optimized, machine readable “object code”. The “object code” (also known as a binary) is a byproduct that can be recreated with the source code. The source code is literally the source of truth.

Sean Grove, from OpenAI, has a provocative thesis. In his recent talk, The New Code, he argues that a well-written prompt (i.e., the spec) is the new source code.

Seen in that light, we’re doing AI development backwards. We craft careful prompts to communicate our intentions to models. The AI generates code. Then we keep the code and throw away the prompt.

"This feels like you shred the source and then you very carefully version control the binary," Grove observes.

Think about that. In traditional programming, source code is sacred. The source contains comments, structure, and documentation—everything needed to understand and modify the system. The binary is just a downstream artifact.

But with AI, we've flipped this relationship. We treat the generated code as the artifact worth keeping and the specification—the prompt—as disposable.

Grove argues this gets it exactly backwards. Code, even elegant code, is what he calls a "lossy projection" from the specification. Just like decompiling a binary won't give you the original comments and variable names, reading code won't tell you the full intent behind it.

The specification, however, contains everything. A sufficiently robust spec can generate "good TypeScript, good Rust, servers, clients, documentation, tutorials, blog posts, and even podcasts."

“A sufficiently robust spec can generate good TypeScript, good Rust, servers, clients, documentation, tutorials, blog posts, and even podcasts.” —Sean Grove, OpenAI

More importantly, specifications do something code cannot: they align both humans and machines on shared goals. Grove puts it simply: "A written specification effectively aligns humans and is the artifact that you use to communicate and discuss and debate and refer to and synchronize on."

He predicts: "In the near future, the person who communicates most effectively is the most valuable programmer. And literally, if you can communicate effectively, you can program."

The new scarce skill isn't coding. It's writing specifications that fully capture intent and values.

For product managers, this should sound familiar. It's what we've always done—just now the machines are listening too.

Wait, didn’t prototypes kill the spec?

Until recently, the product lifecycle had to start with the spec (or PRD or concept doc or napkin) that gets the initial wireframing, designing, prototyping, and MVP development under way.

The traditional approach felt like a necessary evil. Engineers built basic MVPs to get something—anything—into customers' hands. "If you're not embarrassed by the first version of your product, you've launched too late" became gospel.

Our entire approach to building products has recently undergone a significant shift, and in this new world, the spec is often the output, not the input.

Today, you don't need to ship a single line of code to get a prototype into customer hands. Tools like v0, Lovable, and Replit let you build functioning prototypes in hours, not weeks. No engineering required.

This isn't just faster—it's fundamentally different. Armed with a "vibe coded" prototype, you can gather real customer feedback before writing a single line of your feature spec. You can test assumptions, iterate on flows, refine interactions.

The old workflow looked like this: vague idea → wireframes → designs → engineer-built MVP → customer feedback → painful spec revision → wireframes → designs → rebuild → pray.

The new workflow: vague idea → rapid prototype → customer feedback → crystal-clear spec → AI-assisted implementation.

Prototypes haven't killed the spec. They're making specs better.

Spec-driven development in action

Let's look at a hands-on example of how this all plays out. Danny Martinez is the founder of decimals, a platform (in stealth) that enables experts in the creator economy to place talent from their network into jobs.

Are you an AI-first PM looking for a new opportunity? Drop in your details and we’ll let you know when we come across interesting opportunities.

Are you a company looking to hire an AI-first PM? Apply to our talent network and we’ll share a curated shortlist of candidates.

Danny is going to walk us through their spec-driven development process—a process that has had two impacts:

massively improved communication with engineering for the bigger features, and

enabled Danny, despite having no prior coding experience, to go all the way from detailed spec to live feature for the smaller stuff.

Over to Danny…

Here’s a recent example I worked on. For context, we’re building a product that enables expert influencers to place candidates from their networks into jobs. After shipping a new landing page, we needed to give our experts a quick way of accessing the link to their own page.

We need a button in the header that directs to the company-apply page. I'm focused on the emails at the moment. This is vibe code-able if you can pick it up please.

This was from my co-founder, referring to a simple button that needed to be shipped. Easy enough, and precisely the kind of thing that a non technical person can now ship themselves.

Here’s the setup and steps for how this got shipped within a couple of minutes:

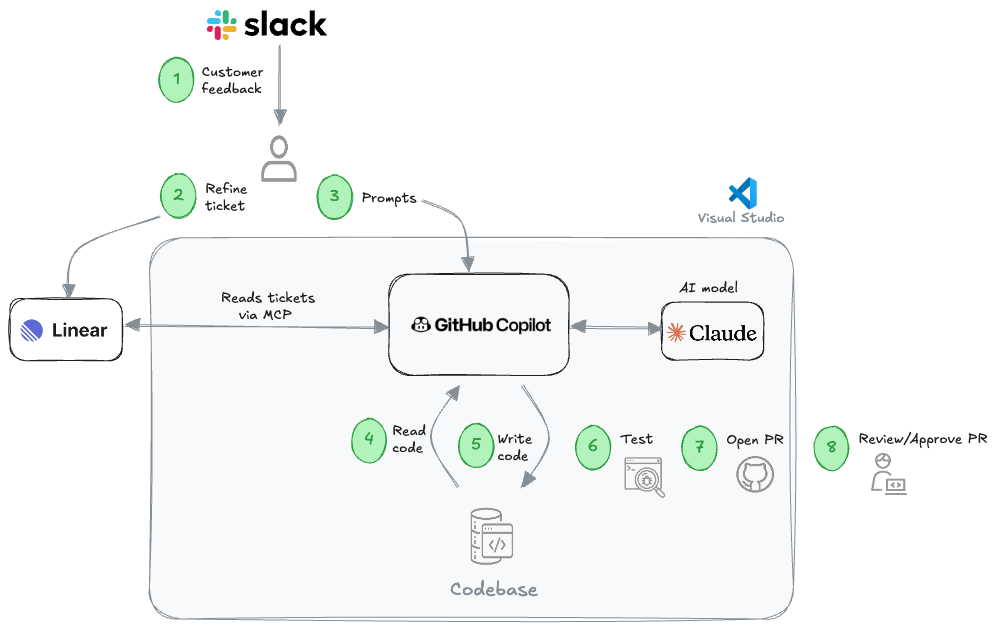

Project management tool: Linear

IDE: VS Code

Extension: GitHub Copilot Pro

Model: Claude Sonnet 4

MCP Server: Linear MCP server to allow Linear tickets to be accessed via Copilot

Let’s take a look at the steps in the process (follow along in the Loom video above):

Generate a Linear ticket out of the Slack message from my co-founder (00:14)

Clarify what I want the new copy to be in the ticket above (00:25)

Open up Copilot and prompt Claude to open up the Linear ticket (01:18)

Prompt Claude to review the ticket and analyse it relative to the codebase (01:52)

Prompt Claude to create a branch and implement these changes (02:30)

Test the changes to ensure they’re working as expected. (02:52)

Open a pull request (PR) on GitHub to ship these changes into the codebase (03:55)

Wait for an engineer to review/approve the PR

Zooming out, the true power of this setup comes into focus. Yes, this is a trivial example, but the point remains: a non-technical person can now go between Linear tickets, a codebase, and an engineer, all with a couple of prompts to Claude via GitHub Copilot.

And again, the critical part of all of this isn’t the code itself: it’s the spec.

Now, it’s important to caveat the above with what’s needed for it to work well:

Being specific: Using vague specs will only result in a messy codebase. Using Claude to take an initial draft of a ticket, review the codebase, and help make it more specific is an essential part of the process. In our case, we also have guidelines for writing a good spec.

Being selective: Using the above for simpler tasks is ideal. The more complex the ticket, the greater the need for someone who knows what they’re doing to get involved (“self-serve” ends up being anything but, in these cases).

Gatekeeping: This approach only works well because there’s an actual engineer who knows what they’re doing, reviewing changes and ensuring the balance between simplicity and functionality is maintained.

But let’s be clear: the rules have changed. Specs are the source of truth for everyone building the product, including the LLM.

With the proper setup, it is entirely realistic to expect to be contributing to a codebase as a non-technical person. With enough time and patience, you can start to understand the codebase and implement changes yourself, rather than simply relying on Claude to bail you out every time.

One day, you might even expect an AI agent to ship your ticket whilst you sip your coffee.

If you’re a PM and worried about what AI is going to do to your job, the key is to realize that the job itself is changing. But that’s also the case for everyone else. The great thing is that the core skills required for an excellent PM are even more valuable in this new world.

As we predicted in a previous post, the companies that are working in this way will need more, not fewer PMs. And it turns out that prediction is working out rather well:

Long live the spec!

William Gibson, the science fiction writer who coined the phrase “cyberspace,” once said:

The future is already here—it’s just not very evenly distributed.

I’m reminded of this when I think about what is and is not possible with AI. Today, AI's gains are profoundly uneven. Some things—generating code, text, images—have made quantum leaps. They operate at AI speed. Other things—talking to customers, discovering their needs, convincing them to buy—still move at human speed.

This uneven distribution is reshaping product teams. The spotlight is shifting from implementation work to understanding work. The core skills that have always set apart the best PMs—understanding user needs, defining problems clearly, designing elegant solutions—have become exponentially more valuable.

The best PMs turn those insights into specs—specifications that align teams, guide implementation, and serve as the lasting artifact in an increasingly automated development world.

Thank you for outlining a problem that is not easily understood! We see it every day at Gluecharm. Specs and how they are done, and with who, are definitely the way forward. Probably the only one!

Agree that specs are an interface to infrastructure.

But specs have never really been about code - they're a proxy for ideas, values, and priorities.

So yes, more people can go from idea to prototype faster. But like you said, the bookends - feedback, trade-offs, decisions - move at human speed.

IMO, that's not a tech problem, it's more of a systems and culture problem.

More here -> https://hchau.substack.com/p/ais-uneven-acceleration