Managing up on high performance teams

How to win trust, get buy-in, and thrive alongside leaders who operate in founder mode.

About a year ago, the idea of “Founder Mode” burst onto the scene when Paul Graham recapped a talk from Airbnb CEO, Brian Chesky. Brian had followed the common advice to hire good people and turn the reins over to them, but found that layers of management slowed things down and blunted Brian’s ability to steer the company.

In “Founder mode for the rest of us”, I discussed the idea that founder mode isn’t reserved for founders. Every great leader I’ve worked with operates with the level of ownership, speed, decisiveness, and attention to detail that defines a good founder. Which means you’ll encounter these leaders throughout your career… and working with them requires a completely different approach.

High-performance leaders demand more than the standard playbook for “managing up”—they move faster, dive deeper into details, and expect you to operate with the same level of ownership they do. In this post, I’ll share what I’ve learned about winning trust, maintaining credibility, and thriving alongside leaders who operate at this intensity.

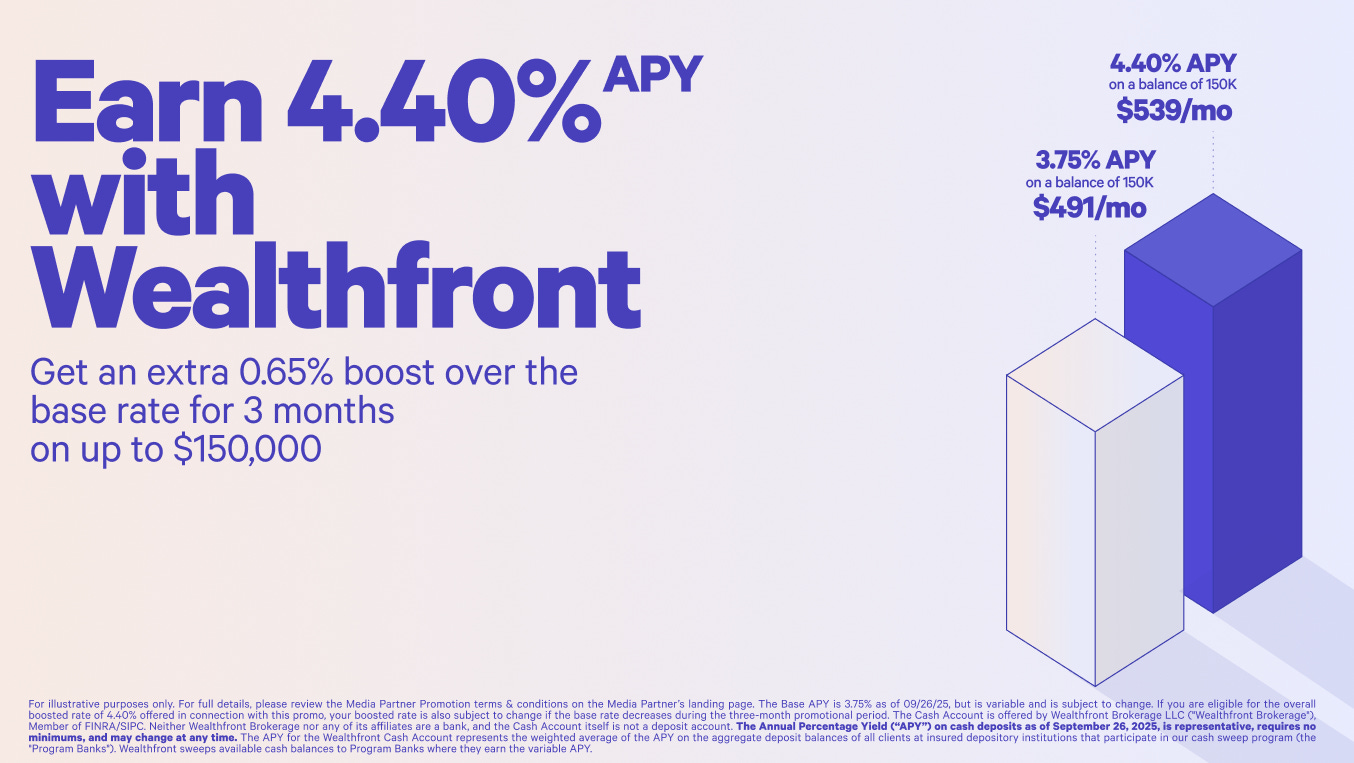

This post is brought you by Wealthfront.

Wealthfront is a tech-driven financial platform with a mission to help people grow their savings into meaningful wealth over the long term. Their high-yield Cash account earns you 3.75% APY from program banks on your uninvested cash – one of the highest in the market – along with stacked features like no monthly fees, up to $8M in FDIC insurance through program banks, and free instant withdrawals to eligible accounts. Right now, you can get an extra 0.65% APY for three months on up to $150,000, for a total 4.40% variable APY when you open your first Cash Account. Promo terms and conditions apply.

Go to wealthfront.com/ravi to sign up today.

This is a paid endorsement for Wealthfront. It may not reflect the experience of other clients, and similar outcomes are not guaranteed. Wealthfront Brokerage is not a bank. Rate is subject to change. Promo terms and conditions apply.

More than busywork

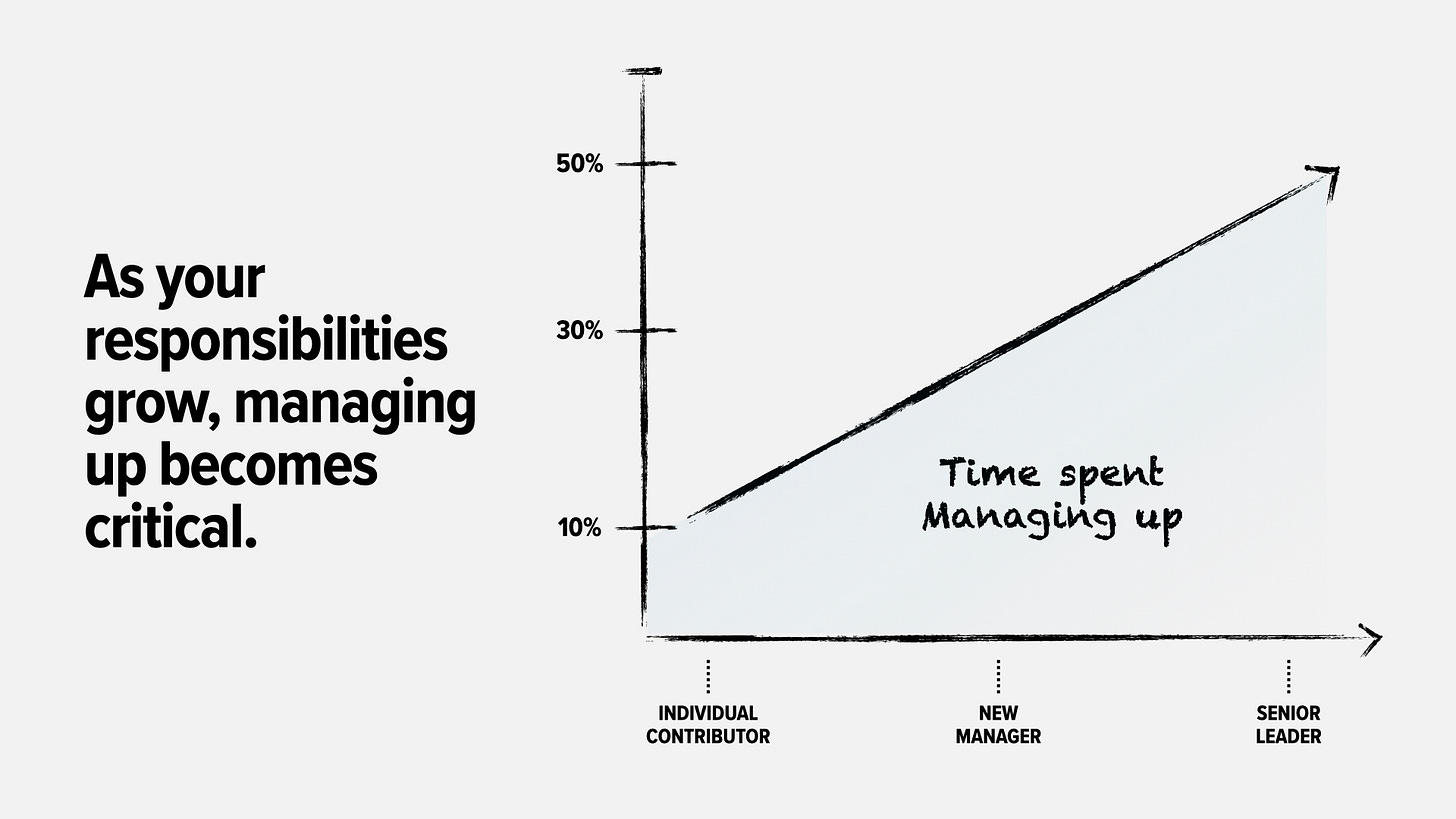

As you get more senior, a frustrating trend emerges: less time with your team, more time aligning leaders and executives:

As an individual contributor, you might spend 10% of your time managing up.

As a new manager, that jumps to 30%.

By the time you’re a senior leader, you’re often spending half your time coordinating with other leaders and executives.

This isn’t busywork—it’s the nature of senior leadership. Your path to success fundamentally changes. Instead of tangible deliverables, your impact is measured in influence.

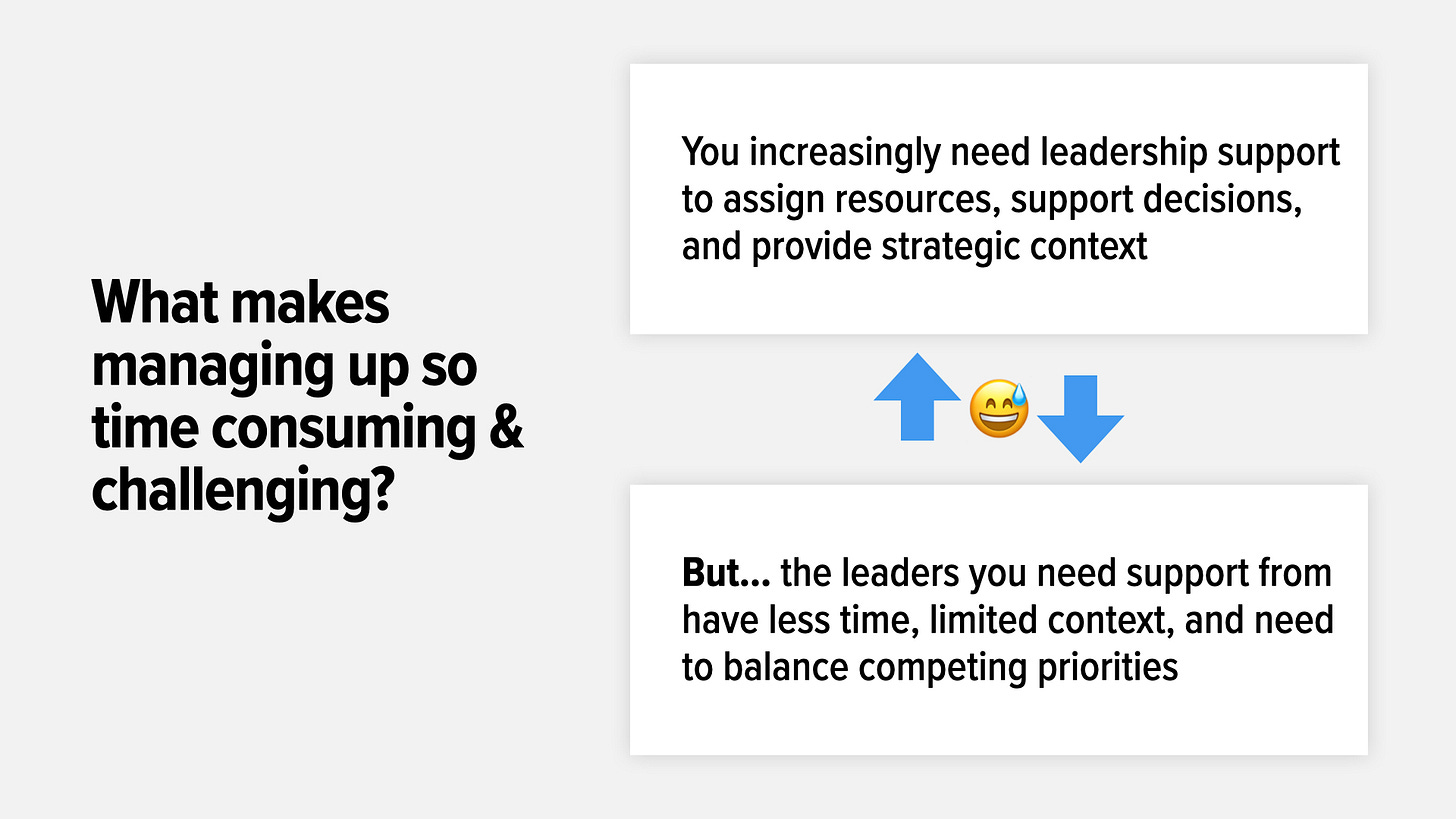

Here’s the tension: You increasingly need leadership support to assign resources, back decisions, and provide strategic context. But the leaders you need support from have less time, limited context, and must balance competing priorities.

These challenges intensify when working with leaders who operate in “founder mode.” They’re context-switching constantly, dealing with challenges you have limited visibility into, and making rapid decisions with imperfect information.

As a result, it can be difficult to get the time and attention you need from executives.

This can be frustrating. Why would a leader ask you to work on something they don’t have time to support?

In a perfect world, senior leaders would be able to give full time and attention to every person in their org and every product initiative. In reality, successful executives instinctively spend their time and attention where they feel it will have the highest ROI.

Managing up is the art of breaking through the noise to convey the value of what you’re working on and get the support you need—and it’s one of the most effective ways to accelerate your career.

Managing up is the art of breaking through the noise to get the support you need.

Let’s look at three habits that help you build strong relationships with high-performance leaders:

Put yourself in their shoes

Foster their confidence in you

Make clear, compelling asks

Habit #1 → Put yourself in their shoes

Few people take the time to understand what it’s like to be an exec at a fast-growing, high-performance company. It’s easy to look at an executive’s title, compensation, and status and think: “I’d be happy to have your problems.”

Some people assume senior leaders have plenty of time to think and coach—that’s their job, after all. In reality, senior execs must switch contexts constantly, ruthlessly prioritize, and end each day knowing they just scratched the surface of what needs their attention.

Elon Musk once reflected on how he spends his time:

“I don’t have a lot of open space. It’s generally back-to-back meetings and it’s insane...my days are like insane torrents of information. I don’t recommend it. I’ve been thinking, how long can I keep this up? Because I don’t want my brain to explode, and the meetings that are scheduled are not just nice-to-have, they’re meetings that are essential.”

Think about what it’s like to be an executive at a high-performing company:

Their day is stacked with 6-8 hours of essential meetings, barely scratching the surface of demands on their time

They receive hundreds of emails daily and spend non-meeting time managing constant information flow

They’re held accountable for aggressive goals, often shaped by factors beyond their control

They’re dealing with challenges you have limited visibility into—reorgs, fundraising, layoffs, poor performers, board meetings

All of this may sound familiar—you may be in the same boat. In the face of these demands, senior leaders need to feel confident their teams are making progress. They gravitate to leaders who worry about the same things, run toward hard problems, and take ownership.

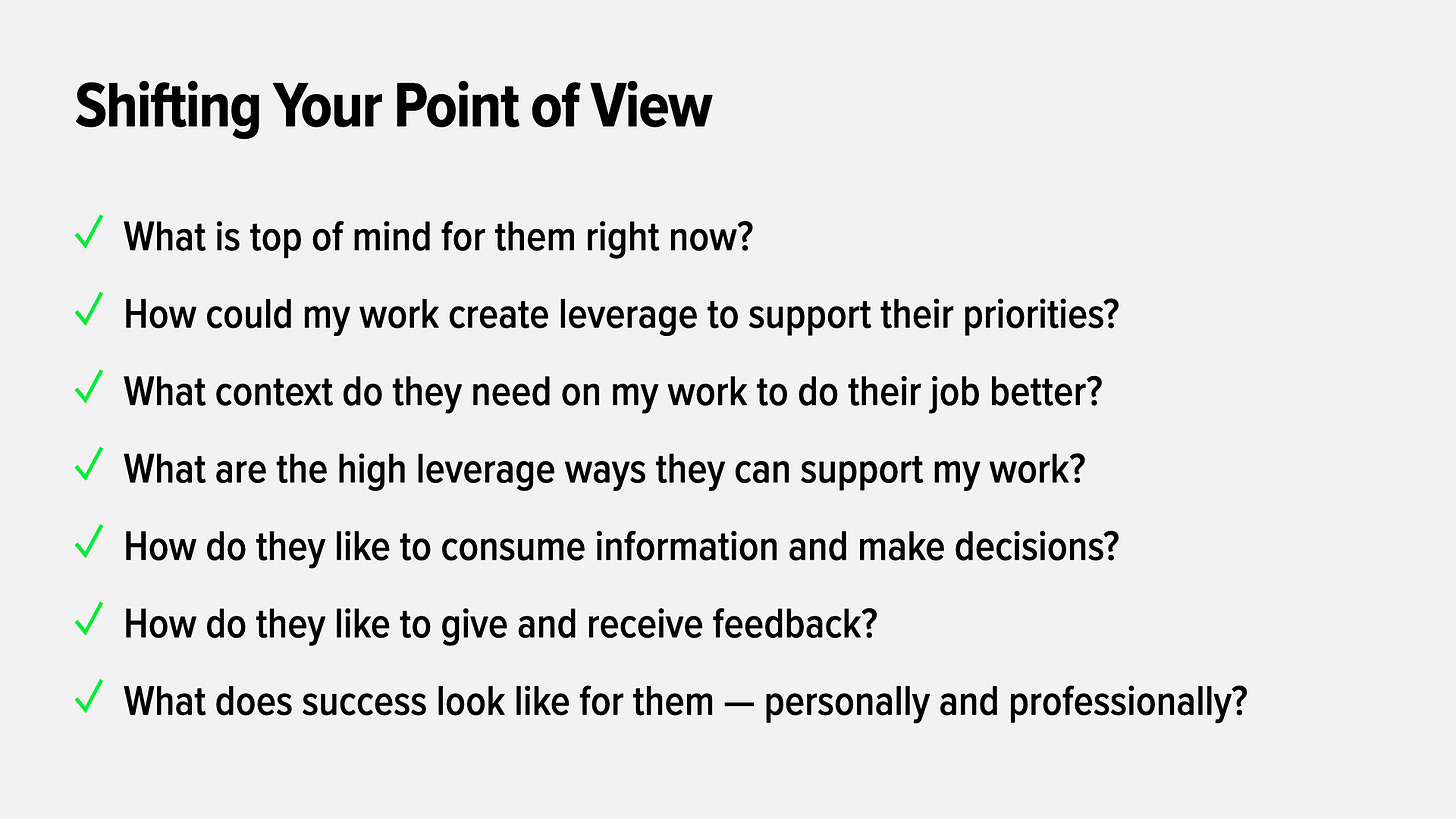

You can foster the right mindset by asking the right questions about your boss and other key leaders:

What is top of mind for them person right now?

How could my work create leverage to support their priorities?

What context do they need on my work to do their job better?

What are the high leverage ways they can support my work?

How do they like to consume information and make decisions?

How do they like to give and receive feedback?

What does success look like for them—personally and professionally?

These questions help avoid a common trap. Many product leaders conflate their priorities with their boss’s priorities, assuming “my success is their success.”

In reality, your boss is facing an array of priorities, constraints, and stressors you don’t see and may have nothing to do with what you’re working on. Shift your point of view and frame your work in terms of how your boss defines success—not what is necessarily best for you and your team.

A few weeks after starting at Tinder, I had a 1-on-1 with the PM leading Messaging. I asked, “What’s the most important thing on your roadmap?”

He paused. “Can I be real? Nothing in Messaging will move the needle. The critical path for the product is before matches even happen.”

Rather than advocate for his team, he shifted to my perspective by asking what was best for the product overall. It served him well. He was the first person I thought of when we needed to build a new pod for one of the most important initiatives in the company.

Habit #2 — Foster their confidence in you

When executives have confidence in you, you’re able to operate with more agency and have a much easier time getting buy-in.

Executives have limited resources to allocate, imperfect information, and are constantly making trade-offs. This can create situations you look around and see resources going to teams that don’t seem like they need them… while your team isn’t getting the resources despite needing them much more.

Getting resources isn’t a matter of being right. There are many competing answers on how to spend resources—all of which seem right depending on your perspective. Resources gather where leaders have confidence.

Executives aren’t asking themselves: Does this team need more resources? (Invariably, the answer is “yes”). Instead, they ask themselves: Where can I deploy limited resources to get the maximum ROI?

Your boss isn’t asking: “Do you need more resources?” Instead, they’ll ask themselves: “Where can I deploy limited resources to get the maximum return?”

Confidence compounds, for good or bad

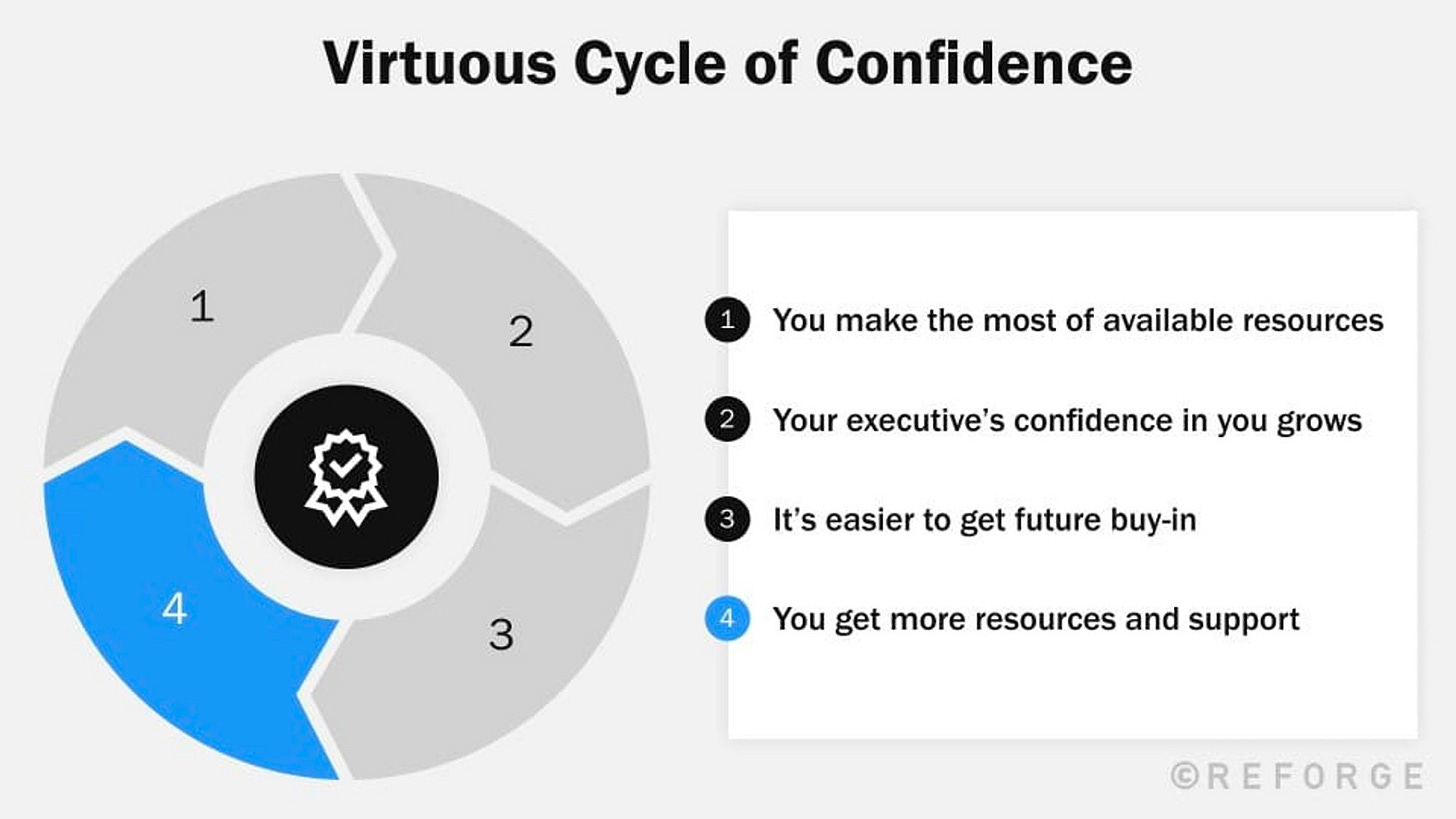

Building executive confidence creates a virtuous cycle: (1) you make the most of the resources available, (2) your executive’s confidence in you grows, (3) it’s easier to get future buy-in, (4) you get more resources and support—and the cycle repeats.

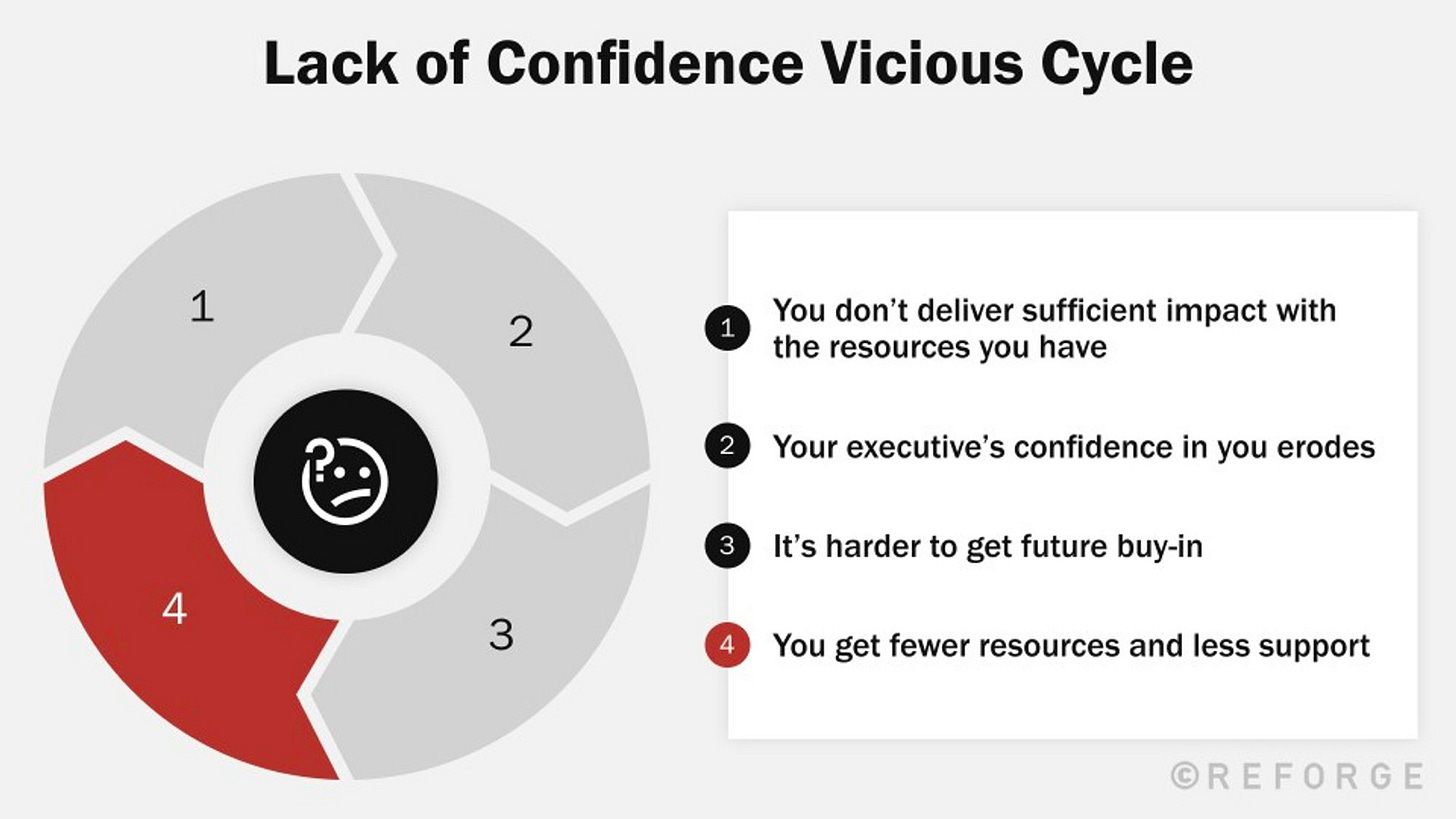

The reverse is also true. A lack of confidence leads to a vicious cycle:

The Credibility vs. Alignment Map

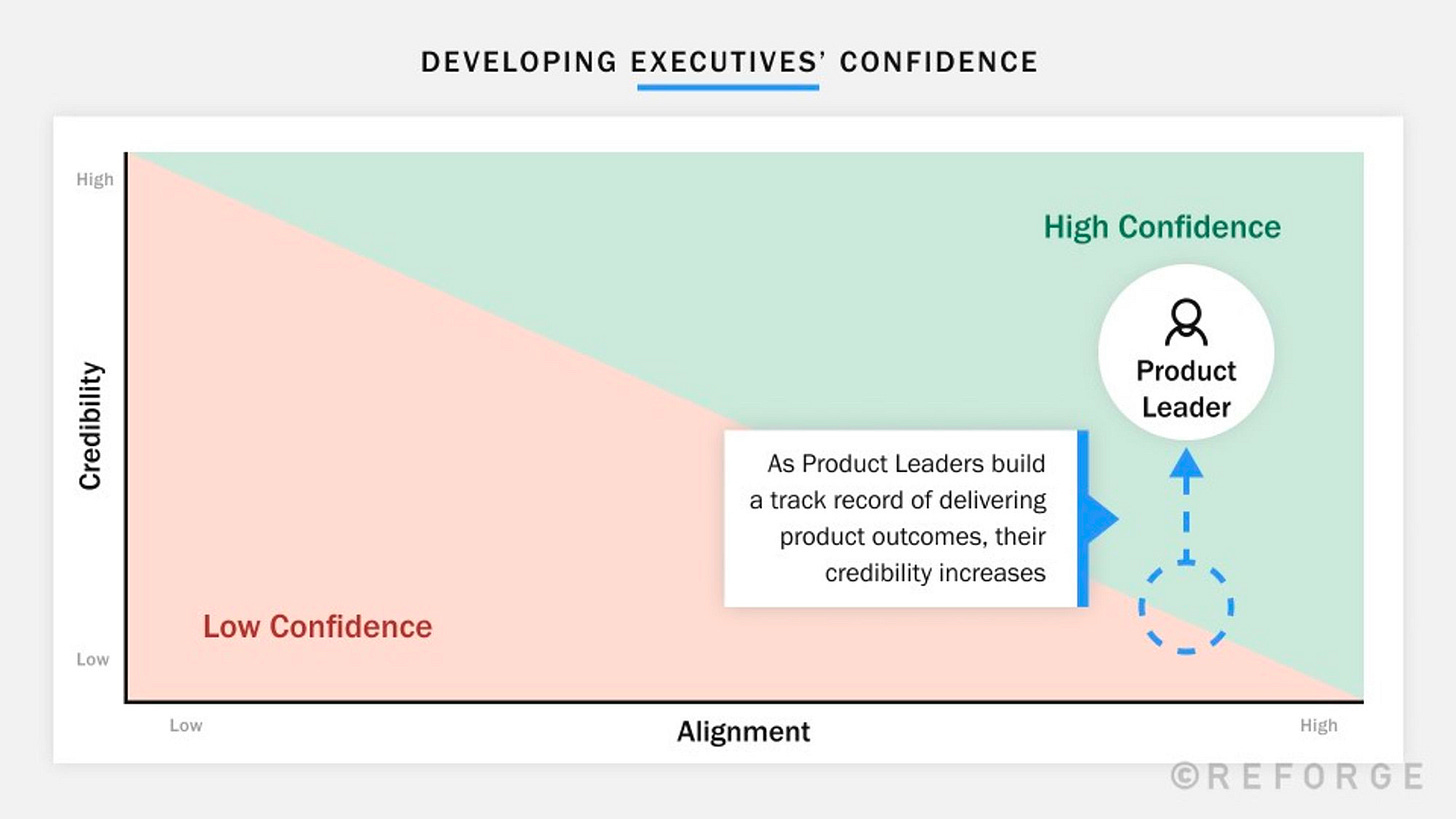

There are two components to developing an executive’s confidence in you:

1. Personal Credibility: How effective have you been in the past when you’ve gotten buy-in?

One of the things that becomes increasingly important as you get more senior is your ability to predict and then achieve the future. Public company CEOs are constantly evaluated on this—they must set quarterly guidance, commit to targets publicly, and then deliver against those commitments regardless of market conditions or unexpected challenges. Missing guidance has severe consequences: stock price drops, board pressure, loss of investor confidence.

This is why CEOs and executives value leaders who can shoulder the same responsibility: forecasting what’s achievable, committing to it, and then making it happen despite changing circumstances. They need people who won’t just try their best, but who can confidently say “we will deliver X” and then actually deliver it.

2. Alignment with Executive: How aligned is what you’re trying to accomplish with what matters most to the executive?

One of the first questions executives ask themselves is: “Is this what I would do if I were in this person’s role?” The closer the answer is to yes, the more confidence they have.

This isn’t about executives micromanaging—it’s about pattern recognition. They’ve built their judgment through years of decisions and outcomes. When you’re pursuing an approach they would take themselves, it validates both your judgment and theirs. More practically, when your work directly connects to their top priorities—the commitments they’ve made to the board, the metrics they’re accountable for—supporting you becomes an obvious decision rather than a risk.

Executives want to see you succeed, and their instinct is that the best way for you to succeed is to do the things that they would do.

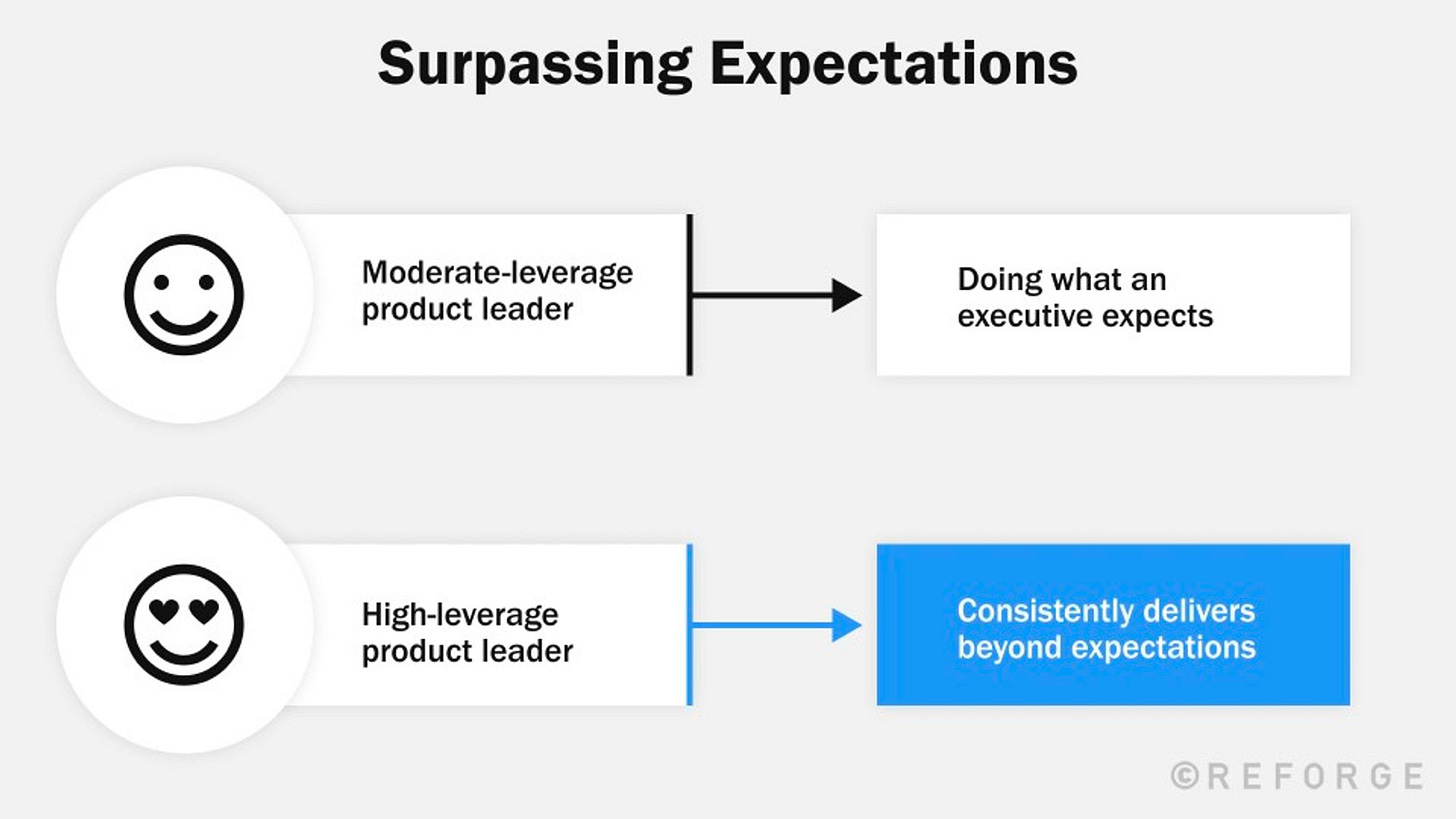

However, the goal isn’t to stay in total alignment. The best product leaders take smart risks and consistently deliver more than what is expected.

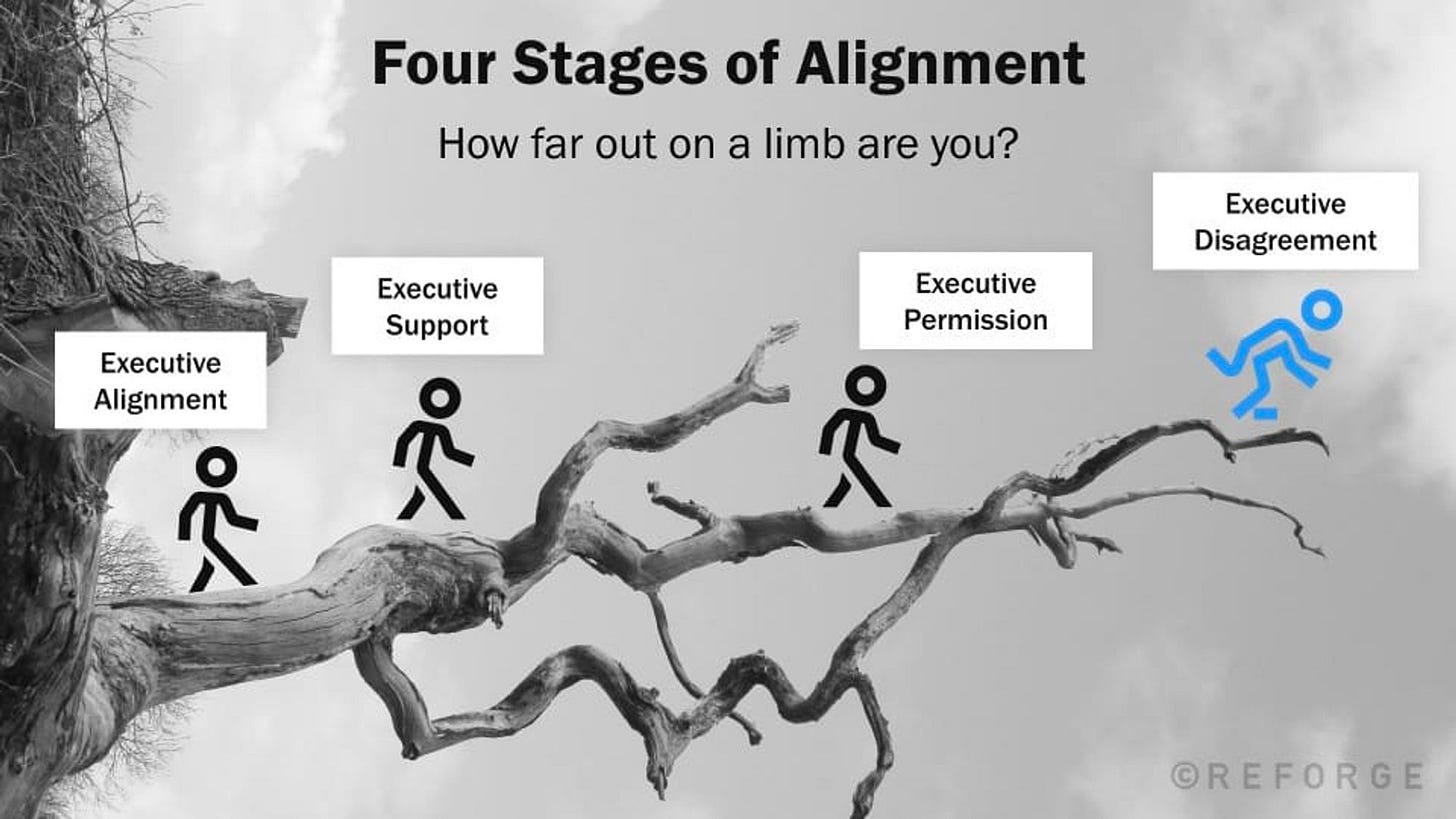

Are you out on a limb?

Taking risks is a dance, because it often means doing things that are out of alignment with an executive’s perspective.

Think of it like going out on a tree limb—there are four stages:

Executive Alignment: You’re not that far out. You’re doing something the executive would do themselves. If it fails, you don’t lose much credibility—the executive views it as their own lapse in judgment.

Executive Support: You go a bit farther out. The executive’s stance: “I don’t know if this is the right thing, but I trust your judgment.” If the initiative fails, you’ll lose some credibility, but it’s tempered by the exec thinking: “I enabled this decision and share accountability.”

Executive Permission: You’re far out on a limb. The executive’s stance: “I don’t believe this is right, but I’ll let you do it.” High risk, high reward. Success impresses the executive with your judgment. Failure costs you significant credibility—the exec thinks: “As I expected, I was right and they were wrong.”

Executive Disagreement: You’re over the limb. The executive’s stance: “I don’t believe this is right, and I won’t let you do it.” This may cost you some credibility depending on how compelling your case was and how well you “disagree and commit.” Persisting after being overruled will further undermine your credibility.

The challenge? You don’t always know how far out on the limb you are. You want to deliver beyond expectations, but you need to do so without eroding confidence.

This is why the Credibility vs. Alignment map is valuable—it helps you navigate that tension. Executives see you as an asset when you either: (1) align to their priorities and help achieve them, or (2) have earned a track record they can count on.

A few years ago, I worked with two Director-level product leaders who started around the same time. Min led a larger team working on what was considered the company’s future. Max led a smaller team working on impactful but less strategic initiatives.

Max’s smaller team delivered immediately. When he saw opportunities to do more, he led with impact: “With more engineers, I can achieve X% more growth.” His team grew slowly—each time, Max achieved more with the additional resources.

Min’s team also delivered, but not as much as leaders expected. She said she didn’t have enough resources and couldn’t do everything being asked. She needed more to do her job.

Her team grew too—after all, she was working on the future of the business. But each time, she found reasons for needing even more engineers, PMs, and designers. Leadership’s confidence began to waver. The CEO wondered why such a large team wasn’t doing more.

Eventually, Min’s team stopped growing, and people questioned whether she was the right leader. Max took over parts of her team, and Min’s career stalled.

For Max, the virtuous cycle was in full motion—he became one of the most senior executives at the company. Min got caught in a vicious cycle that undermined her promising career, despite outward signs of success like a growing team.

Habit #3 → Make clear and compelling asks

As we discussed earlier, “managing up” is ultimately about getting the support you and your team need to be successful. When making asks of executives, your job is to help leaders help you.

Maybe this sounds familiar: you’ve painstakingly defined a plan and you’re simply looking for approval to kick-off. Instead, your boss or others offer a raft of unrelated or distracting ideas. You leave the meeting without the approval you need and with more unanswered questions than when you entered.

A common saying goes: “When given a choice between A or B, most senior executives will choose C.” Execs are trying to add value with limited context, so it’s not surprising that they try to provide feedback from first principles rather than “sticking to the script.”

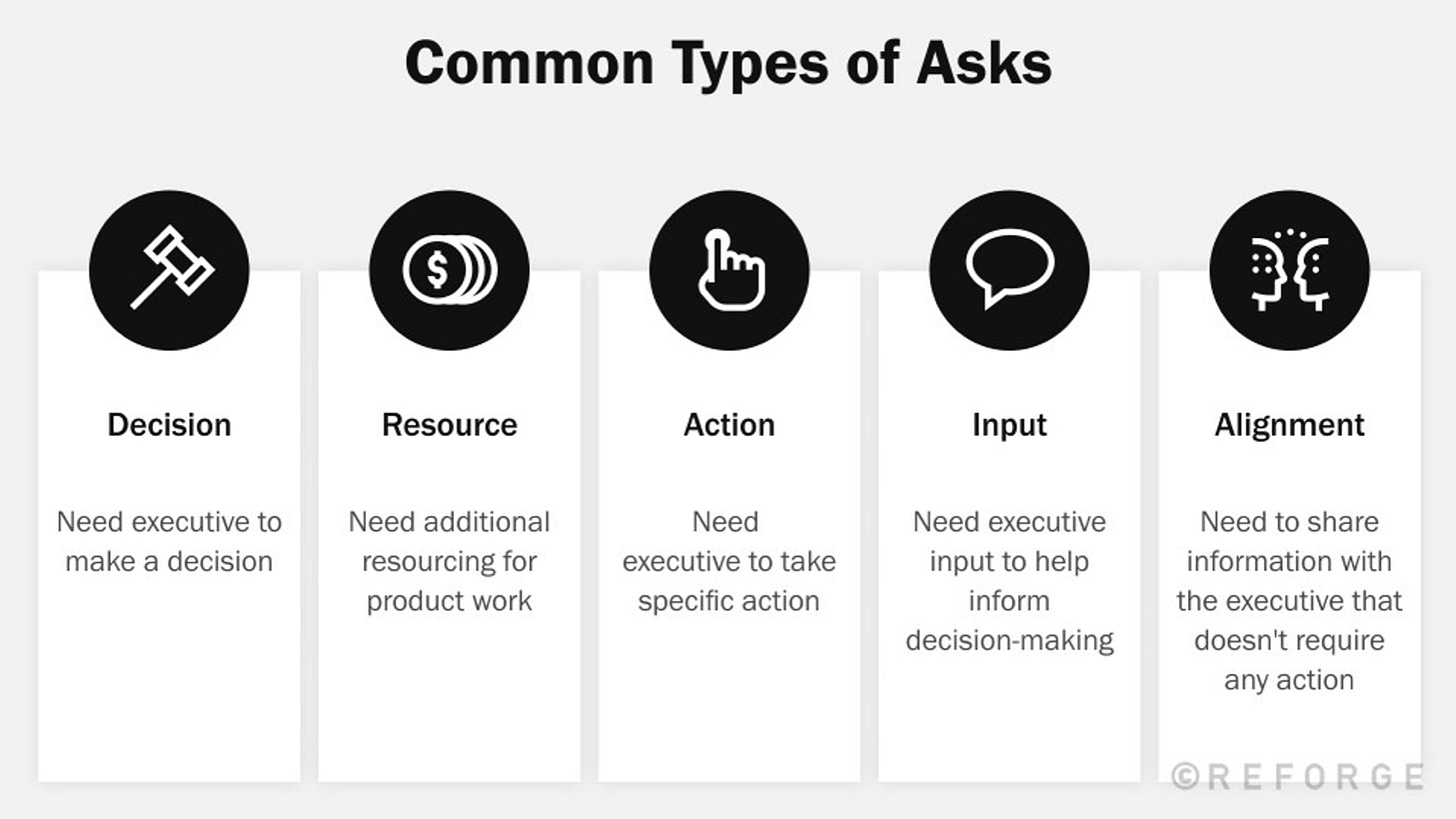

Be clear: what are you asking for?

The first step is to be clear about the scope and purpose of your ask. This focuses leadership’s attention on what matters most.

There are five ways executives can provide value, and each requires a different conversation. Making it clear what kind of discussion you want to have sets the stage for an intentional discussion rather than a general one. Here are the five most common types of asks:

Decision: Need executive to make a decision (e.g., should we prioritize customer segment A or B?)

Resource: Need additional resourcing for product work (e.g., approval to hire another PM)

Action: Need executive to take specific action (e.g., approving a promotion for a higher performance)

Input: Need executive input to help inform your decision-making (e.g., context from the latest board meeting)

Alignment: Need to share information with an executive that doesn’t require any specific action (e.g., flag a performance issue that may require future escalation)

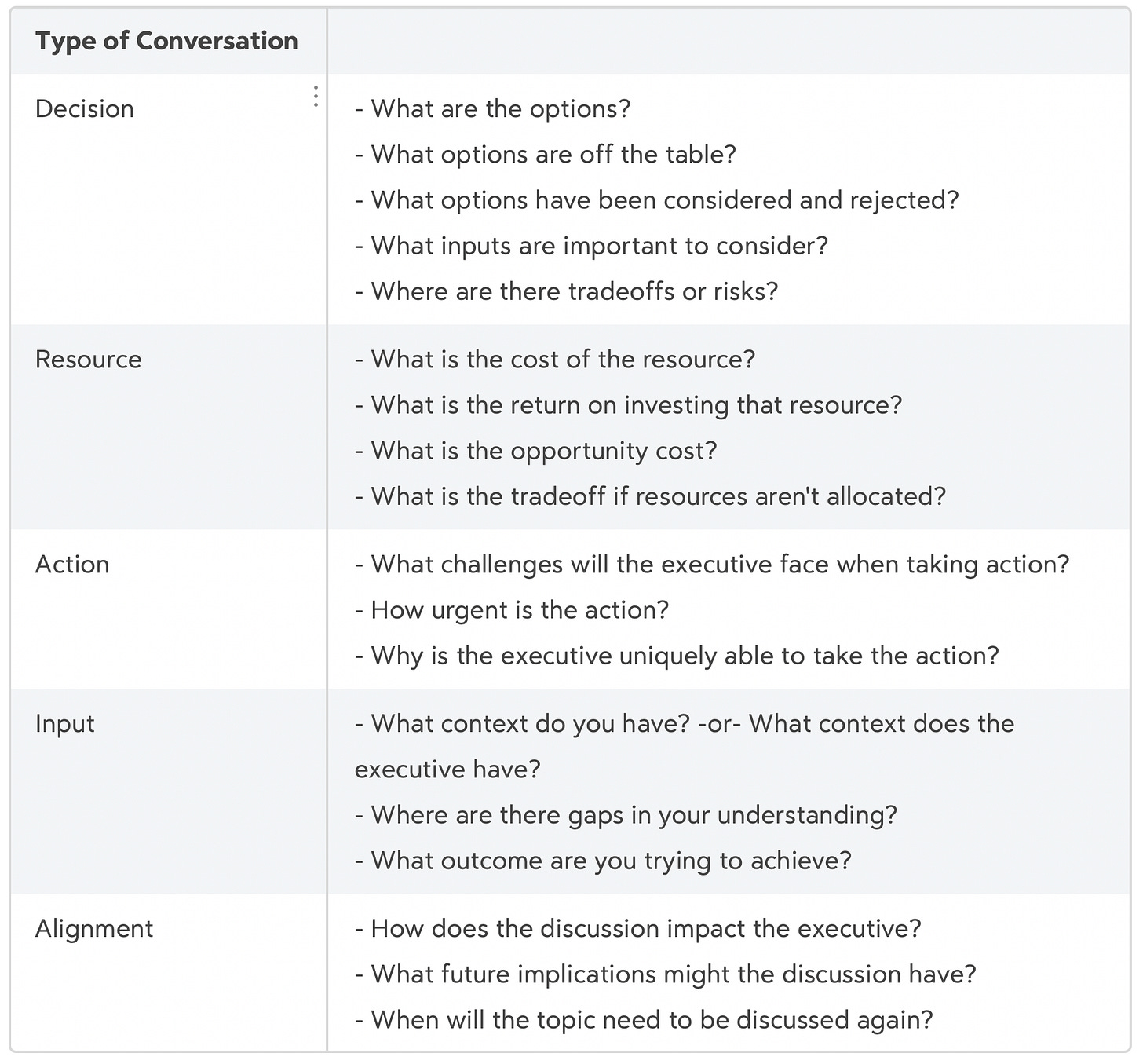

Provide the context necessary to make a decision

Next, prepare the right context. Tailor what you share to the specific ask. Overloading executives with irrelevant details can overshadow the key points you want to communicate.

I’ve seen talented leaders derail executive reviews with irrelevant details, discarded options, and caveats. The detailed thinking that helped them arrive at a clear decision overwhelms a brief meeting, and executives leave more confused than confident.

Below are key pieces of information needed for each type of conversation:

Decision

What are the options?

What options are off the table?

What options have been considered and rejected?

What inputs are important to consider?

Where are there tradeoffs or risks?

Resource

What is the cost of the resource?

What is the return on investing that resource?

What is the opportunity cost?

What is the tradeoff if resources aren’t allocated?

Action

What challenges will the executive face when taking action?

How urgent is the action?

Why is the executive uniquely able to take the action?

Input

What context do you have? -or- What context does the executive have?

Where are there gaps in your understanding?

What outcome are you trying to achieve?

Alignment

How does the discussion impact the executive?

What future implications might the discussion have?

When will the topic need to be discussed again?

Provide space for discussion

Your job is not to be right or get what you want.

Your job is to lead a conversation that helps leadership make the right decision for your company, even if that may not be the decision that you want for your team. Regardless of the outcome, leaders will appreciate the thoughtfulness, collaboration, clarity, and openness you’ve brought to the conversation, and they’ll know that they can turn to you to move the needle on important areas for the business.

In making asks, I often see folks fail on either end of two extremes:

Over-dependence. Some product leaders want prescriptive direction from executives. They’re hesitant to take action without explicit alignment, so they ask for detailed direction on what to do. But executives don’t have bandwidth to provide great direction like this—they’re distracted by competing priorities and need you to drive ideas forward. These “high maintenance” leaders become low-leverage.

Over-independence. Other product leaders go the opposite direction, minimizing inputs from executives altogether and bringing them “solutions not problems.” But this makes you a “low-visibility” leader. Executives become disconnected from your work, and over time their confidence erodes—they wonder what’s really happening and whether you’re on track. When you turn them into “approvers” rather than “collaborators,” you miss their most valuable contribution: the judgment and pattern recognition they’ve built over years. The goal isn’t to avoid executive input—it’s to amplify it.

Match leadership’s intensity

Managing up with high-performance leaders isn’t about managing their expectations—it’s about matching their intensity and making them more effective.

Resources & support flow to people who are aligned with leadership’s priorities and have earned their confidence.

The best product leaders I’ve worked with don’t view managing up as a chore or political maneuvering. They see it as a core part of their job—giving leverage to the executives they work with, so those executives can give leverage back to them. That’s how you build the kind of trust that lets you operate with real autonomy, even on the highest-performing teams.

This post is brought you by Wealthfront.

Go to wealthfront.com/ravi to to get an extra 0.65% APY for three months on up to $150,000 when you open your first Cash Account.

If you are eligible for the overall boosted rate of 4.40% offered in connection with this promo, your boosted rate is also subject to change if the base rate decreases during the three-month promotional period.

The Cash Account, which is not a deposit account, is offered by Wealthfront Brokerage LLC (”Wealthfront Brokerage”), Member FINRA/SIPC. Wealthfront Brokerage is not a bank. The base 3.75% Annual Percentage Yield (”APY”) on cash deposits as of September 26, 2025, is representative, requires no minimum, and may change at any time. The APY reflects the weighted average of deposit balances at participating Program Banks, which are not allocated equally. Funds in the Cash Account are swept to Program Banks where they earn a variable APY and are eligible for FDIC insurance. Conditions apply. For a list of Program Banks, see: www.wealthfront.com/programbanks. FDIC pass-through insurance, which protects against the failure of Program Banks, not Wealthfront, is not provided until the funds arrive at the Program Banks. While funds are at Wealthfront Brokerage, and while they are transitioning to and/or from Wealthfront Brokerage to the Program Banks, the funds are eligible for SIPC protection up to the $250,000 limit for cash. FDIC insurance is limited to $250,000 per customer, per bank, regardless of whether those deposits are placed through Wealthfront Brokerage. You are responsible for monitoring your total deposits at each Program Bank to stay within FDIC limits. Wealthfront works with multiple Program Banks to make available up to $8 million ($16 million for joint accounts) of pass-through FDIC coverage for your cash deposits. For more info on FDIC insurance coverage, visit www.FDIC.gov.

Instant and same-day withdrawals use the Real-Time Payments (RTP) network or FedNow service. Transfers may be limited by your receiving institution, daily caps, or participating entities. New Cash Account deposits have a 2–4 day hold before transfer. Wealthfront does not charge fees for these services, but receiving institutions may impose an RTP or FedNow Fee. Processing times may vary.

Thank you, Ravi! This is one of my most challenging growth areas, and I appreciate your thoughtful and actionable advice.